SPOILERS all the way. I’m not kidding. Consider yourself duly warned.

The vampires in Sinners do not represent white supermacy per se. At least, not in a definitive form, insofar as vampires CAN be definitive metaphors of any kind.

Because white supremacy doesn’t need supernatural gilding to appear menacing, devouring and oppressive, even in Ryan Coogler’s triumphant and moreish genre exercise – blending Jim Crow-era realism with the baroque stylings of an action-horror romp. The covert Klansmen implanted at the periphery of the film, and whose role culminates in the latter half of the third act, embody the most prosaic kind of evil imaginable. But this doesn’t make them any less of a threat. If anything, they have one advantage over the nocturnal bloodsuckers – they can roam freely over any territory both day and night, invited or otherwise.

No, the vampires here – at least their leader, Remmick (Jack O’Connell) – are simply the manifestation of yet another fallout of systemic oppression. Remmick is of Irish origin and speaks to the suppression of the magical power of his own region’s folk music by the imperialist lurch of both Christianity and the English.

And for sure, a white man wanting to assimilate and fold blues musicians into his ‘rainbow coalition’ project that would seek to upend mundane oppressions with a new vampiric world order does also speak to another layer of exploitation faced by our black protagonists.

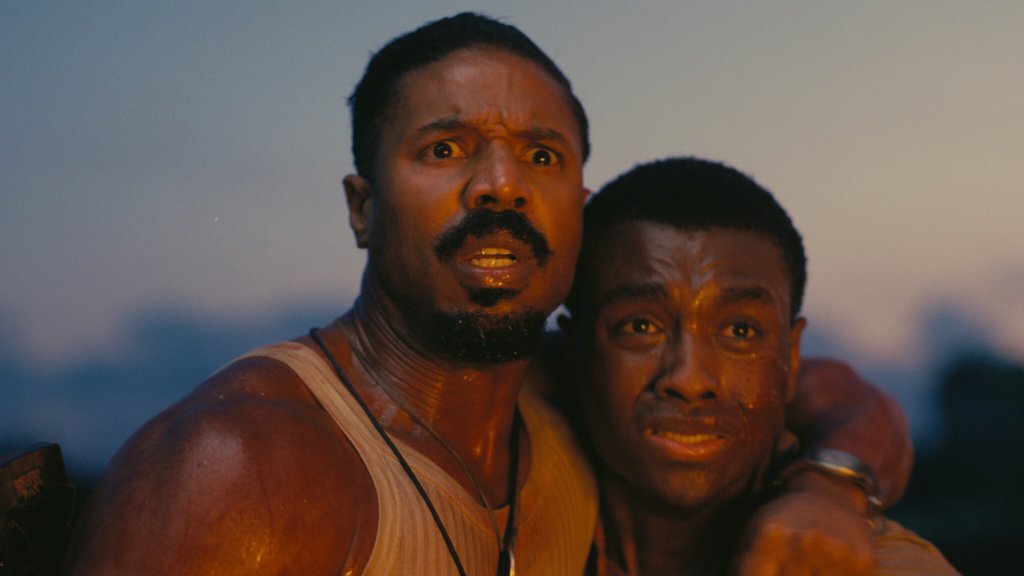

But what’s also interesting here is that it’s Remmick who is given the role of ‘too-radical villain’ who may have “a point” but whom nobody in their right minds would follow to the end. Compare this to Coogler’s mainstream breakthrough, Black Panther. In it, we have Killmonger, played by Sinners’ own Michael B. Jordan, who responds to bigotry in kind, but whose actions ultimately have to be dialed up to an unjustifiable extreme for Marvel’s status quo to be maintained.

Sinners never allows for such a boring return to old tropes. Nobody is a saint here, for sure, barring perhaps young Sammie (Miles Caton), but only because this is something of a coming-of-age story for the musically gifted preacher’s son, whom the ordeal leaves “wiser and sadder” and allows him to gradually make a life for himself as a musician further down the line (transforming into Buddy Guy, no less in a mid-credits flash-forward sequence).

Though hardly the ‘alpha’ of the story, Sammie is the hero here because he manages to slink out of the oppressive binaries imposed by his world. He rejects his father’s pious cocoon, but he also grows out of wanting to be like his cousins – Jordan’s twins Smoke and Stack, whose return to their hometown after a stint with Capone in Chicago kicks the whole shebang into being.

But the undercurrent of sadness that we still feel envelop Sammie at the end – which Smoke warned him about, and which animates the spirit of blues either way – is, I think, down to the loss of the rhapsodic community spirit that we glimpse for a brief, glorious moment when the Twins’ project appears to be succeeding in what it’s trying to do – a sequence in which Sammie’s public debut as a musician ushers forth a wall of sound that pulls in musicians from past, present and future; a chorus which busts open the gates of perception and plucks at one of the animating chords of the universe.

But instead, we find him playing to appreciative but fragmented audiences in a cosmopolitan jazz bar in the big city.

White supremacy has allowed for neither the black community to exist and thrive in peace, much in the same way it crushed the pre-Christian Irish communities attuned to a sense of the numinous that would likely be branded heretic at the drop of a Pope’s hat.

It leaves us scrambling for scraps, and we’re often left scrambling alone.