A couple of months ago, one of the most exciting voices in weird fiction at the moment – Molly Tanzer – kindly passed on an advance review copy of Swords v Cthulhu, a new anthology she co-edited with Jesse Bullington for Stone Skin Press. Published at the tail-end of July, the 22-story-strong collection mashes ‘swift-bladed action’ with HP Lovecraft’s cephalopod alien-cum-existential dread milieu to great effect, to the point where I was inspired to review every single story in the anthology. Now, I (virtually) sit down for a chat with Molly and Jesse about the ins and outs of the anthology, and what it was about the concept that really got them going.

Lovecraft anthologies are a dime a dozen these days. How did you set about to make Swords v Cthulhu as fresh as possible?

Jesse Bullington: It always comes back to the authors, doesn’t it? So long as you have a wide array of interesting voices engaged with the project you can make any subject feel fresh and exciting. To that end we knew from the beginning that in addition to inviting certain authors we wanted an open reading period for submissions – some elements you know you need from the very start, but others you don’t recognize until you see them.

Molly Tanzer: I’d like to add that when it came to soliciting authors, we wanted a mix of people known for their S&S, as well as authors who write horror or fantasy, just to keep the tone different piece to piece. We also found a delightful amount in the slush, that was super-hard, just so many unique and interesting twists, that it was difficult to make calls sometimes. I was really impressed by the range and talent we acquired one way or the other for this book.

The world of genre small press can be dangerously insular: a tight-knit community where – thanks to the internet – everyone knows everybody else. How did you avoid the pitfalls of what could amount to nepotism when selecting the tales in the anthology?

MT: I wasn’t too worried about it. For one thing, we held open submissions, and took a ton from the slush; for another, we had a lot of material to choose from, so the competition was pretty fierce. We rejected friends and accepted people we’d never heard of; we also accepted friends and rejected strangers. Sure, we know a lot of the folks we accepted, but I think the individual stories’ quality speaks for itself.

JB: Yeah, and then there’s the fact that when you’re working as a pro writer and editor you make a lot of friends because you love their work. The vast majority of the friendships I’ve made in this industry have grown out of an appreciation of an individual’s writing, so if I were to never publish someone I’ve come to know personally I’d be cutting myself off from many of my favorite contemporary writers.

Molly Tanzer

The predecessor to Swords v Cthulhu within the Stone Skin Press stable was Shotguns v Cthulhu. With their in-yer-face mashing together of genre-furniture with Lovecraftiana, these titles suggest pulpy fun above all: they’re great attention-grabbers. Do you think your collection in particular offers something more than just pulpy comfort reads, however?

JB: Before saying anything about our anthology I think it’s worth noting that Shotguns v Cthulhu was far from a straightforward action anthology. Editor Robin D. Laws had some fast and fun pulp yarns in there, sure, but there are plenty of brains to go with the brawn (Ekaterina Sedia’s weird wartime tale and Nick Mamatas’s kung fu headfuck immediately jump to mind, for example). So with Swords v Cthulhu Molly and I were very much trying to live up to Robin’s precedent of providing depth, variety, and style as well as action and monsters…but plenty of those, too!

MT: Pulp and comfort reads are two things that are very individual and difficult to define—like pornography, you know it when you see it. I mean, many people probably find the 1982 Conan the Barbarian pulpy, but every time I watch it I’m moved and reminded of what’s important in life. So, whether the book provides more than pulpy comfort seems like something for readers and critics to decide, more than its editors.

Is ‘swift-bladed action’ something you seek out in your own reading? Are you fans of swords-and-sorcery and the kind of historical fiction that the authors in this anthology draw from, and if so, what would you say are its main pleasures?

MT: I read a little of everything, but yes, fantasy and historical fiction make up a large part of it. I’m actually doing a series over on Pornokitsch right now, with Silvia Moreno-Garcia, where I’m reading (and she’s re-reading) the first four Gor novels. In the latest of those, there’s a war between hyper-intelligent, technologically advanced praying mantises and cloned human slaves armed swords and makeshift spears. That sounds far more awesome than what is actually happening in Priest-Kings of Gor, but that’s neither here nor there. Anyway, when I’m done with that, the next thing in line is Amy Stewart’s Lady Cop Makes Trouble, so yeah, I was very pleased to see our authors draw on everything from the English Civil War to far-flung planets more metal than any mind of man could comprehend.

I suppose historical and fantastical fiction provide pleasures both similar and different to any well-written novel or short story—that of stepping outside one’s life for a few moments to experience another. Fantasy gives us barbarians and/or dragons and/or wizards and/or whatever; historical fiction provides us fancy dresses and/or interesting archaic weapons and/or insight into our past, but to me it still comes down to getting acquainted with characters and seeing what they’ll do when stuff happens to them, no matter what sort of stuff it is.

JB: I also read a ton of fantastical and historical fiction, and for the same reasons. I’m in agreement on the source of much of their appeal, too – the only thing I’d add is that I think when we read fantasy or historical fictions we often see the conflicts as being far more dramatic but also more clear-cut than those in our own lives. Even though no sane person would want to actually solve their problems with a sword, it can certainly be an appealing daydream otherwise!

Jesse Bullington

The 22 stories that comprise this anthology are an eclectic bunch, to be sure. But we’d be lying if we don’t say that some recurring themes, motifs and general narrative set-ups didn’t stick out: the colonial milieu in both Ben Stewart and A. Scott Glancy’s story, for example, along with the literary revisionism of Natania Barron and Carrie Vaughn. Did you engineer these commonalities yourself, when you were selecting the stories that would finally end up in the anthology? And if not, why do you think authors were drawn to these motifs in large numbers? That is, what do you think it is about the ‘Swords v Cthulhu’ brief that inspires writers to chase these particular storytelling elements?

JB: We selected individual stories based on their own merits, and of course our taste as editors. As for why certain themes and motifs appealed to the contributors, I’m sure it varied from individual to individual and I’m reluctant to speak on behalf of anyone but myself. Sorry if that sounds like a cop-out!

MT: Jesse and I spent quite a bit of time mulling over our submission guidelines because we wanted to make it obvious what we were looking for. We had a vision in mind for the book, after all! Given our mutual love of fantasy and historical fiction, we suggested those approaches (among others).

Given that you’re both writers of fiction in your own rights, what kind of creative kick does editing an anthology give you that writing fiction from scratch can’t?

MT: Well, the pleasures of curatorship, I suppose. Sure, when I write a story or a novel, I’m arranging and compiling and creating, which all overlap with editing, but it’s internal rather than external. Doing that for others was a new thrill for me – this was my first anthology – but turning a skill set over and looking at it in a new way was something I enjoyed very much.

JB: Editing someone else’s fiction is an entirely different animal than editing your own, and if it affords a special kick I suppose it’s being able to identify areas for improvement without actually having to fix them yourself!

Do you think the small press genre fiction community is in a healthy place at the moment? What advice would you give to writers who are just starting out, or trying to break into the scene in which you guys are active?

MT: This is a hard one. Everyone in publishing, whether they’re with a small press or are publishing with the Big 4, can have only a keyhole perspective, though of course the size of that keyhole is highly variable. I think that the small press scene can be a great and vibrant place full of the weirder stuff you might not see coming out elsewhere. This isn’t to say big publishers won’t take on risky books, but… you see the problem here! Publishing is huge, everyone has their own perspective, and you can’t say much without massively qualifying it.

As to writers trying to break into the scene… what I have to say isn’t going to be too different than anyone else. Value yourself and your writing. Submit to the markets you read, and furthermore, submit strategically, either top-down or best-for-you-first. Be wary of promises that seem too good to be true, and ask for advice if and when you need it, preferably from people who you know are reliable, and who have similar careers to what you want for yourself, or broad experience.

JB: Haha, yeah, I don’t know if I’m in any position to comment on the state of any community! There are a lot of great books coming out through a lot of different small presses, so that’s good, right? Beyond that I think I’ll just second Molly’s assessment.

Advice for starting writers is an easier answer: stop spending all your time reading goddamn advice about writing and just fucking write! Do it all the time! Why are you still reading this interview when you could be writing? Wriiiiiiite!

Now if only I could follow my own advice…

What’s next for you?

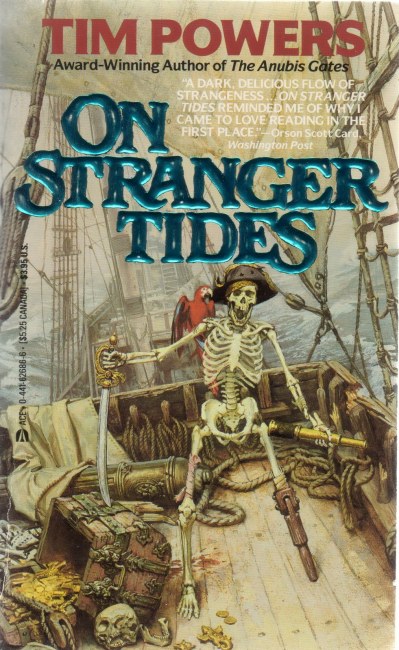

MT: A few things … a standalone reprint of my novella Rumbullion: An Apostrophe will be published this year (it was previously collected in my out-of-print collection Rumbullion and Other Liminial Libations), and next year will see the publication of my second anthology, a cocktails-and-flash fiction book called Mixed Up!, which I’m co-editing with Nick Mamatas. Also, either late next year or early 2018 my novel Creatures of Will and Temper will be published, which is a sort of feminist retelling of The Picture of Dorian Gray, but with epee fencing and diabolism and sisters arguing with one another.

JB: I’m currently completing revisions on the concluding novel in my Crimson Empire trilogy, which has been coming out under the pen name Alex Marshall. It’s a sprawling work of dark fantasy that should be solidly in the wheelhouse of anyone who appreciated Swords v Cthulhu…I hope!

Check out Swords v Cthulhu on the Stone Skin Press site. Meanwhile, click here to read the reviews of the 22 individual stories in the collection.