As outlined in an earlier post, in the coming weeks I will be dedicating an entry to each story in the new anthology Swords v Cthulhu, edited by Molly Tanzer and Jesse Bullington and published by Stone Skin Press. My reviewing method will be peppered with the cultural associations that each of these stories inspire. These will be presented with no excuse, apology or editorial justification.

Two Suns over Zululand by Ben Stewart

Ordo Virtutum by Wendy N. Wagner

The terrors of Lovecraft are a flexible bunch. Because Cthulhu and his fellow eldritch pantheon have no affiliation to established religious creeds — and are more or less stand-ins for the cosmic indifference of the universe to human foibles, though that’s not all they are — they can easily be applied as the antagonistic entity of choice to stories set within any country or cultural milieu.

Wagner and Stewart’s stories in particular play on the notion of the Great Old Ones infiltrating a particular social space, and the hook and twist of the stories lies in the way in which their writers manipulate our expectations of how these micro-worlds would deal with the Cthuloid threat.

Stewart’s story plunges us straight into a reconnaissance mission embedded within the Anglo-Zulu War, and on the face of it, Stewart appears to be attempting a piece of full-blooded historical war fiction of the kind we’ve already seen earlier on in the anthology with A. Scott Glancy’s Trespassers. But the real thrust of the story is more straightforward, as our protagonist, Lwazi, is told in no uncertain terms that he must retrieve the idol of ‘H’aaztre’ — an obvious stand-in for Lovecraft’s Hastur diety — from an Englishman who has it in his possession.

If Lwazi fails in his mission — as he is told by the mentor figure Mandlenkosi — they will be powerless to stop a cataclysmic event triggered by these otherworldly dieties.

Stewart wastes no time in laying out the raison d’etre of the story, and even has Mandlenkosi plainly declare what Lwazi must do in direct speech. This evokes a similar ‘gamified’ effect as other stories in the collection, and it matches the enjoyably direct, unpretentious thrust-and-parry of the rest of the tale.

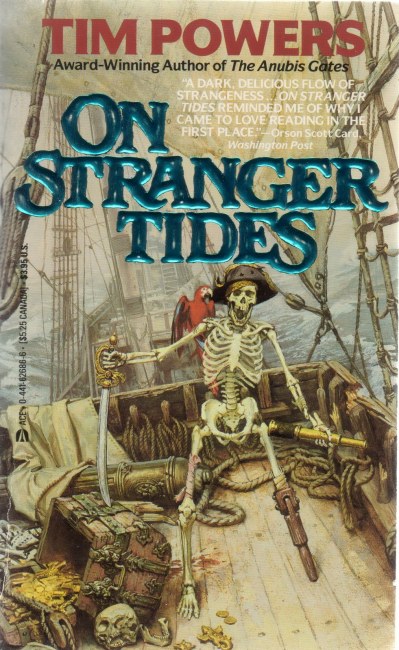

Défense de Rorke’s Drift (detail) by Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville

And in a strand that once again brings to mind Glancy’s story, the threat posed by ‘H’aaztre’ and everything he’s set to unleash trumps the ‘mundane’ struggles between the Zulus and the British. Though the details of these particular monsters and how they operate are influenced by Lovecraft, it must be said that the ‘common enemy who unites us in the end’ is a familiar trope to the alien invasion genre. And more than gods, Lovecraft’s creatures are alien invaders — albeit ones that tend to inspire cult-like fervour among a select group of maddened devotees.

This fervour is the engine of Wagner’s story, which takes the striking historical personage Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) as its main inspiration: in fact, the title refers to a famous piece of music by this German Benedictine abbess — who apart from being a mystic and polymath was also a composer and writer.

Hildegard von Bingen

Wagner is clearly infatuated with Bingen, and has no qualms about casting her into what amounts to a badass superheroine role in the story. But what’s more interesting is how Wagner builds the clerical world that Bingen belongs to — suggesting its political and social structure, and Bingen’s role within it, before it is undermined by an eldritch-struck outsider.

Though Lovecraft himself was often lost inside the rabbit hole of his psyche — which was in turn hemmed-in by his oft-discussed prejudices — these writers are adding colour and specificity to the cosmic horror that lies at the core of his work.

Read previous: Caleb Wilson, Nathan Carson & Orrin Grey