Horror writer T.E. Grau is slowly but surely carving a niche for himself as one of the most eclectic and artful practitioners of the genre in the American scene, as is borne out by his critically acclaimed debut collection The Nameless Dark — which we reviewed right here just a couple of days ago. Now the man himself steps into the Soft Disturbances interview lounge to give an expansive, generous and impassioned overview of what inspired him so far, and what we can expect from his upcoming novella, They Don’t Come Home Anymore…

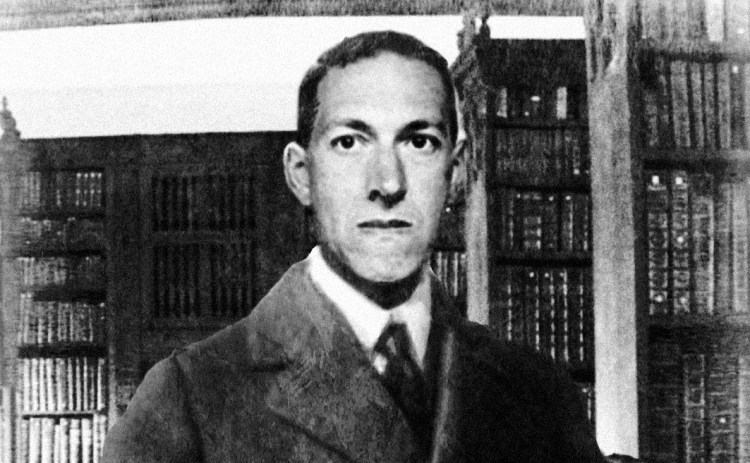

T.E. Grau

When did you first realise that you wanted to start writing fiction, and did you act on this impulse immediately?

From as far back as I can remember, I had an interest in writing, and starting in my early teens, I fostered a nebulous, long-range plan for engaging in the serious authorship of fiction at some unspecified date. But instead of hunkering down and just doing that, I spent decades dancing around the edge of the well, writing everything else but fiction, including music journalism, review work, two different humor columns, tech writing, ghost writing, and dozens of intensely mediocre screenplays.

I think what held me back was I thought I needed to write a novel to be an author, and I didn’t have any ideas for a novel that were worth a damn, other than some bullshit pseudo-Hunter Thompson tale about an American drifting to China to document the last vestige of the American Dream on the opposite end of the world. It would have been awful.

At the tail end of 2009, while I was writing one of those intensely mediocre screenplays – which just happened to be for a horror film for which I was brought in to “add in some Lovecraftian elements,” as I had read and greatly enjoyed HPL’s work back in college – my wife Ivy changed the course of my creative life forever. She’d read some of my scripts, and enjoyed some of the exposition (overly long as it was), but also saw that the medium wasn’t a good match on either end.

HP Lovecraft

Finally, as I was complaining about yet another round of ridiculous producers’ notes and re-writes on a script that probably wasn’t going to get made anyway, she said, “Why don’t you just stop with this screenwriting and write fiction?” That was it. No one had ever asked me that question before. Not in the 11 years I’d written scripts, nor the decade before while I’d written everything else, futzing around for local arts magazines and live music journals. The simplicity of her question – which hit my ears as a statement – was astounding. That I could just walk away from a medium into which I’d invested over a decade of my creative life but also grown to loathe, and finally pursue something that I’d always dreamed of doing. I “quit” screenwriting that very day, and Hollywood somehow plodded onward without me.

While reading and researching Lovecraft’s work for the script I’d just been working on, I’d discovered that there was such a thing as “Lovecraftian fiction,” stories written as pastiche, inspired by, and/or set in the universe created by H.P. Lovecraft. I had no idea this was a thing. But poking around a bit more, I found out that there were anthologies looking for short stories of Lovecraftian fiction, and that an editor (and RPG icon) by the name of Kevin Ross was looking for stories for his antho Dead But Dreaming 2, to be published by Miskatonic River Press (Tom Lynch’s outfit).

I think I’m a better writer because my journey to prose took so long, during which time I wrote for very few readers in a wide range of styles

I saw that as my shot to break in. I didn’t need to write a novel to be a prose writer. I could write a short story, and ease my way into the fiction game. Find out if I have a knack for it, and then see what happens. I started writing ‘Transmission’, then started writing ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’ almost simultaneously. I pitched both to Kevin, and he vibed better with ‘Transmission’, so I finished the story and sent it to him, and he accepted it. My first completed, and purchased, piece of fiction. I held back ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’ for five years, and first published it in The Nameless Dark: A Collection, even though it was initially written in early 2010.

So, my journey to prose was a long time coming, but I think I’m a better writer because it took so long, during which time I wrote for very few readers in a wide range of styles, and mainly due to the constant rejection one faces as a screenwriter. In film (not television), the writers are on the very bottom rung, and receive no deference and very little respect for their integral contribution to the content-making process.

That was important for me to experience, if only to get over myself and realize my fingers don’t weave gold with every keystroke. Ivy working with me as my editor was the other important factor, allowing me to finally understand that the fine tuning is just as or more important than the initial burst of creativity. That not every sentence (or paragraph or page) is precious and sacred. Defensive writers aren’t great writers. Confident writers kill their babies, because they’ll always make more. She taught me that, and I owe her everything because of it.

Why is horror such an appealing genre for you, both as a reader and writer?

I think you’re either born a person who digs the darkness or you’re not. And I don’t necessarily mean people who play Halloween dress-up every day, favor goth fashion, live as wanna-be vampires, practice Satanism, or something similar.

That’s cool and all, if that floats your boat, but what I’m talking about is someone who has a genuine interest, fondness, and deep affection for things that reflect a melancholy, a gloom, a doom, a general decay and reflection of mortality or pessimism. Things that are just a bit askew from the norm. The incomprehensible or the unexplainable. Liminal places of abandonment and decay. Rain clouds and fog. Desolate fields. Ruined buildings and oddly constructed houses. The vastness of outer space. Magnolias draped in Spanish moss. Mausoleums. Subterranean places. Attics. Abandoned barns and industrial sites. Vast stretches of trees. Cheap carnivals. Ancient caves at the bottom of the sea. The beautifully grotesque and the (Big G) Gothic.

The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli

These are the essential salts, the foundation elements, of horror and fantastical fiction. It either appeals to a person or it doesn’t. You can’t force it, you can’t fake it (although some do try).

And while I’m a generally upbeat and affable person, my mind and curiosity and sense of wonder call out to those things, and when I encounter them, while most would be saddened or creeped-out or uncomfortable, they make me happy and content.

I feel at home. That’s what draws me to horror literature, and to those who can capture this sense of gloomy atmospherics, dread, and impending doom in the stories they write. There’s nothing quite like that. It’s a true power.

There are many definitions of the ‘weird fiction’ genre (which you’re also associated with). What’s yours?

I get uncomfortable with the various labels going around for what I like to call “dark fiction,” as I think people spend too much time trying to create then box-up subgenres of fiction for discussion or marketing purposes, or just for “team-ism,” which is rarely productive or positive. But I do like the term “weird fiction,” as it nods to the late 19th and early 20th century authors, including all of those amazing pulp writers, who added so much to fantastical fiction.

Weird fiction to me is also defined by a literary streak, a core of elegance and elevated prose, which usually brings with it a sense of restraint in terms of blood, gore, or even death

Weird fiction to me is work of writing that introduces the unexplained – and usually unexplainable – into our rational world. It can – and often is – laced with the scientific, the religious, the historic, and the cosmic, taking real world facts and beliefs and twisting them just a bit, then setting them back on the shelf to distract our eye, as something just doesn’t seem right about them anymore. It’s peeling back a common facade and finding something unexpected and unknown underneath. It’s the odd, the uncanny. The bizarre.

Also, and this is just a personal opinion, but weird fiction to me is also defined by a literary streak, a core of elegance and elevated prose, which usually brings with it a sense of restraint in terms of blood, gore, or even death. Weird fiction can be quite subtle, but no less impactful in terms of unsettling a reader.

Would you agree that Clive Barker and Nathan Ballingrud are among the most powerful influences on the stories collected in your debut collection, The Nameless Dark? If so, why?

Clive Barker certainly isn’t an influence, as I had never read any Barker until the stories for The Nameless Dark were either finished and published in other places, or already plotted out. I didn’t read Baker during his heyday in the 80s, as I was still geeking out over high fantasy and sword & sorcery. The closest I came to horror was Conan books.

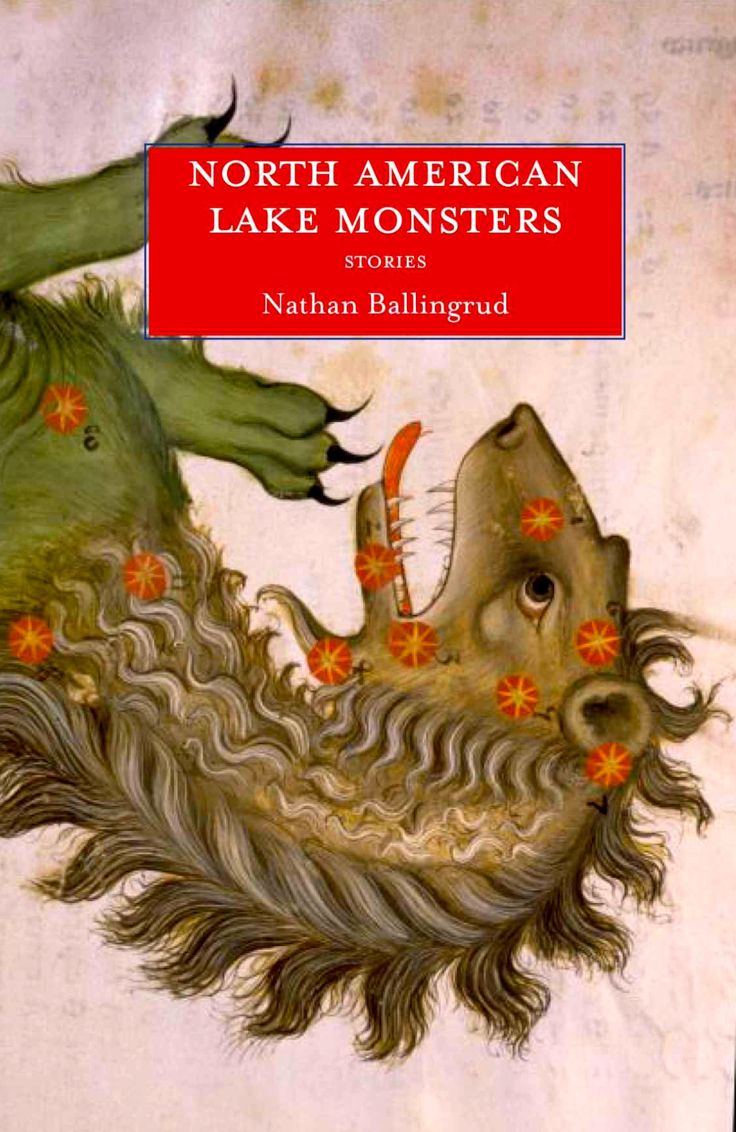

Nathan’s work isn’t so much an influence either (as, similar to Barker, most of my stories for my collection were already either finished or plotted when I read his work for the first time in North American Lake Monsters), but his writing was and is very important to me in terms of what the genre of dark/horror/weird fiction is capable of in this new century.

No one writes with more honesty, and can inspire more discomfort, than Nathan Ballingrud

So, in many ways, he’s not an influence so much as an inspiration, as the fearless exploration of guilt, shame, embarrassment, and generally horrible behavior that lies at the heart of many of his stories hit me like discovering a new color. I was floored when I read his collection. Still am. No one writes with more honesty, and can inspire more discomfort, than Nathan Ballingrud. He’s also a genuinely scary writer, meaning he writes things that scare or disturb me. I rarely experience that reaction when reading anyone’s work.

Barker is great (particularly his shorter work, like ‘In the Hills, the Cities’), and his Hellraiser universe is a horror staple (co-opted by Hollywood), but in many ways, I think Ballingrud is a superior writer to Barker, although I understand it’s difficult to compare based on time periods and conventions of the respective eras.

Long term, and deep down into my marrow, I’m probably more influenced by Hunter S. Thompson, Vonnegut, and Beatnik writers than anyone in horror fiction, although Lovecraft certainly influenced several stories expressly written for Lovecraftian anthologies, some of which ended up in The Nameless Dark.

The figure of Lovecraft looms over many of the stories too. Does the fact that there are plenty of Lovecraftian ‘markets’ open at any given time play a part in that? Or have you always been attracted to the core of Lovecraft’s work?

I covered a bit of this above, as Lovecraftian fiction was my entry into prose writing, and horror writing in particular. Regardless of how I feel about him personally, his work got me into writing fiction, which literally changed my creative life, and I’m grateful that he drew from and coalesced many of his influences (Bierce, Poe, Dunsany, Chambers, etc.) into the multiverse and mythos he created.

Cthulhu in R’lyeh by jeinu

What originally drew me into his work was his sense of cold cosmicism, and a universe that is far more vast and malevolent and uninterested in our existence than our puny, needy human intellect can comprehend. There is no devil, no angels, no bearded man pulling the strings. There are no strings. Just endless voids, with the occasional Outer God and Great Old One brushing against our reality just long enough to influence primal cultures, establish secretive and murderous cults, and burst minds by their very existence. I loved this. It was very dark and menacing, very secret history and cryptozoological.

Growing up in a staunch, Evangelical Christian home, the stuff I was fed in church always chaffed at the back of my lizard brain. Stumbling across Lovecraft’s outlook on the universe was a revelation, and a breath of fresh, clean, pessimistic air. I was hooked instantly.

My most recent, current, and upcoming work doesn’t and won’t contain nearly the level of Lovecraftian influence, but his work will always feature somewhere in my writing, especially in my Salt Creek stories, a novel for which I’m slowly putting together.

A satirical edge is also present in a number of the stories, mainly focused on certain aspects of American culture that seem to irk you. Were there axes you needed to grind before you set out writing some of these stories?

Before writing fiction, I wrote comedy for years, in various mediums with varying levels of success. I’ve been doing it much longer than writing dark fiction, so humor or satire is going to naturally bleed into my writing where appropriate (and maybe where it’s not).

I do have a lot of frustration, and even some bitterness, about various aspects of American culture

I’ve never thought of my satirical viewpoints as grinding axes, per se, but I do have a lot of frustration, and even some bitterness, about various aspects of American culture, and humanity itself. Hyper-religiosity, racism, misogyny, stinginess, greed, bad parenting, predation, xenophobia, and just general shittiness to others gather at the top of a very long list of grievances against my species.

Okay on second though, I’m grinding several axes. I’d guess dozens of axes are being ground at any one given time, depending on how many stories I’m working on at the same time.

Could you tell us something about your upcoming novella, They Don’t Come Home Anymore? How would you say it builds on your previous work?

I always have a hard time summing up the novella without giving anything away, but here goes a weaksauce attempt: It’s a story about teenage obsession, conformity, parenting, class, and illness providing a backdrop for a somewhat jaundiced, slightly different take on the contemporary vampire tale.

I’m not sure how or if it does build on my previous work, although it is set from the POV of a teenage girl and follows her around in the world. In this way, it reminds me a bit of ‘Tubby’s Big Swim’, as it includes a bit of geographical wandering, which set the plot framework of ‘Tubby’.

I see it as something I’ve never done before (and probably won’t do again), marking my first and probably last vampire tale. Also, it’s my longest piece to date, which shows some building on my previous work.

And the cover – featuring artwork by Candice Tripp and cover design by Ives Hovanessian – is an absolutely stunner. I count myself incredibly fortunate to feature such a cover as the calling card for the novella. Candice is doing the artwork for my second collection, and we have another project in the works, as well. Crossing my fingers that I’ll be working with her for many years to come.

And finally… what advice would you give to writers keen to break into the weird fiction and/or horror scenes in particular?

First of all, write what you want to write. Truly. Honestly. Dig down deep, cast your gaze out as far as you can, and get it all out. Question everything, follow all leads. Don’t worry about genre or market or anything out of your control. Until you get paid for it as an employee with a parking pass, bathroom key, and benefits, don’t think of yourself as a “commercial writer.” Think of yourself as a writer, period, which means you write for you.

There are very few money-making fiction genres, and weird and horror fiction aren’t it

Make yourself happy and creatively satisfied, because if you’re writing weird fiction for money, a) you’ll fail in reaching your goal, because no one really makes any money, and b) your writing will come off as lackluster and passionless, which will make you even less money and lead to more failure. Don’t do that to yourself.

There are very few money-making fiction genres (and maybe one – romance/erotica, and I suppose whatever “literary fiction” is), and weird and horror fiction aren’t it. So, if you choose to write down here, crouched low in the shadows with the rest of us ghouls, do it for the right reasons. Do it for the love of the shade, the decay, the destitute and the forgotten. Do it to celebrate the beauty of the dark.

Then, get to work, and look for open markets. I’d hazard that with self publishing, online publications, and a recent proliferation of ‘zines and anthologies and fiction journals devoted to weird, horror, and dark fiction, it’s easier to place ones work these days than probably ever before in the history of written language. The markets are there. Write your best stuff and send it out.

And, in the end, if no one will publish you, publish yourself. Get your book on a shelf – YOUR shelf – and on Amazon, in indie bookstores and libraries, and build your legacy, if only for you and your loved ones. Gatekeepers are helpful, but they are not absolute. If you have the talent, the desire, and if you work your ass off, no one can hold you back from becoming a writer of whatever fiction you want to write, written however you want to write it. Very few of us are professionals, but a lot of us are writers. And there’s room for more.

Featured image: ‘Swallowed by the Ocean’s Tide’ by Ola Larsson