Some months have passed since my dad died and it’ll surprise no-one that I’m still processing everything that happened and that in many ways, the full realisation of the loss hasn’t hit me yet, and likely never will.

I’m also envious of those who could find it in them to mourn in seemingly more direct ways – bursting into tears as soon as they heard the news, or crying at any mention of him after the fact.

There’s a lot to be said about your brain working hard to “protect” you from being hit by the news that the person you’ve known since birth – someone who’s played a fundamental part of your life for 38 years – is now no more.

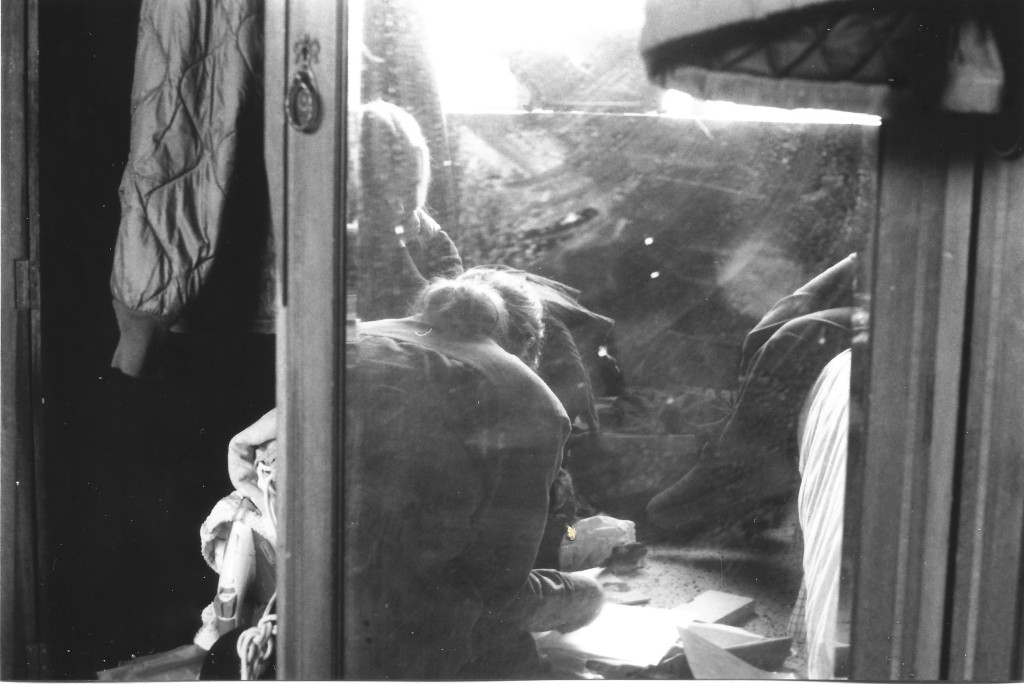

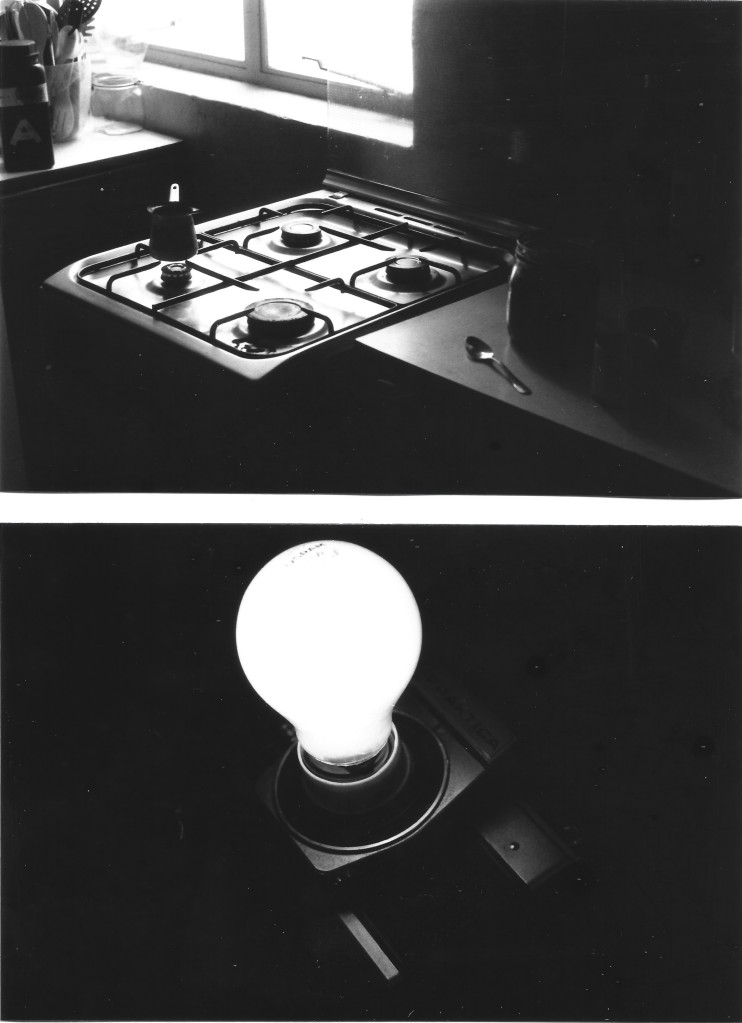

They are literally nowhere to be found in the living, material realm. You cannot hear them, smell them, touch them and certainly no longer hug them hello or goodbye. You cannot gossip with them, you cannot chastise them and you cannot show them affection nor expect any in return. You cannot visit them just to spend time with them – not even a wordless visit during which they click away at their computer and yawn between puffs of ultimately lethal cigarettes.

But this isn’t the worst of it, because this is all, still, the present – or at least, the very recent past. This is how I remember my father moving (sluggishly as it may be) and operating in the final years of his life. No, the torrential waters that the brain’s dam is desperate to keep at bay are the waters of layered history. Because my father was many things to many people, but to me he was dad, and that’s a multitude which contains many other multitudes within it.

A similar realisation hit me after my mum suffered a stroke which would plunge her into a coma that lasted a decade. A person is precious because they are a universe. A parent, in particular, exists as a storied shelf of memories and interconnected thoughts and behaviours; ones which continue to evolve and reverberate from each other while the person is still alive, but which are then frozen and ossified by proxy after they’re removed from the realm of the living.

This is where they can become mythologised if we’re so inclined. To some of us, or in some of our moods, this is also a site where it becomes easy to cast judgement with an illusion of rigid finality. You can draw definitive conclusions and cast a final verdict, now that the accused – or the lauded – is no longer around to contradict you.

In my father’s case, it is also about the extolling and fetishisation of an artist’s way of life. It’s so tempting to view the motor of this work as something which emerges from outside the common fold and which we can simply gawp at like it’s an alien diamond put on display just for us. As if the material conditions matter not a jot. As if he was given a gift and simply executed it with generous grace – bestowing his lessons onto others too, so that they may take some of the diamond for themselves.

It’s this abdication of the possible and the practical which allows many people to live in a similar phantasmagorical plane that my father occupied in the latter years of his life.

In any contemporary society dictated by the norms of neoliberal capitalism, living “free” means living at the expense of others – or of your own wellbeing and stability. It’s kill or be killed, eat or be eaten, and when you’re not eating others, well… then you just have to eat yourself. My father chose to bite the bullet of precarity and to swerve out of the neoliberal order instead of meeting it halfway. He spent his time making beautiful work which my siblings and I will now endeavour to protect and preserve. A sizable effort which will also require us to undertake an additional – and equally onerous – side-quest: finding help which is truly trustworthy in an island beset by mercantile souls in search of their next host.

I am also dreading each passing day, because I suspect that the worms will come out of the woodwork good and proper once they decide the grace period has passed and they are within their rights to come knocking at our door demanding the pieces of my father he often gave all too freely when he was around.

Because the phantasmagorical state means that people are not only free to romanticise him, but in that romanticisation – a swerve away from reality and into the same cloudy realm in which he’d made his home – they can reassess and re-engineer their own relationship to him like a piece of Lego. If all is true, everything is permitted.

So we had a situation where people that I know for a fact meant to do my father both reputational and financial harm in the recent past, had no qualms about showing up to his memorial and even posting and boasting about it on social media – lest the FOMO get too much and they be excluded from the collective chant they’ve been called to participate in… a blitz in which genuine tributes collided directly with vainglorious, self-serving bandwagon-jumping.

Being an artist means that you’re public property to a certain extent, and my father’s accommodating nature meant that everyone had their own piece of his memory to take home with them. But it’s a piece free from the vicissitudes of the raging torrent that the dam is just about keeping steady for me.

Crucially, it’s a piece that may be small but it illuminates quite a bit, blessing the keeper with a selective blindness. So we would be forced to parse through DMs from apparently well-meaning Senders but whose content was so blisteringly insensitive it was difficult to even believe a human being took the time to type them out and hit ‘Send’. Like the Sender who, for example, implied that they should be the ones to archive my father’s work as they suspected that the family would be tempted to just leave it to rot somewhere.

In this instance, the family becomes secondary – lumpen byproducts of the artist’s creative process, clearly ill-equipped to handle his legacy because they weren’t seen to be going through the usual motions that fellow darkroom acolytes went through, and posted incessantly about on their socials.

In a lot of ways, this is a crucial consideration because it cuts to a deeper vein of my father’s life, work and his appeal to many.

It is down to that hopelessly fraught term: authenticity.

Many have extolled his sincerity, generosity and his apparent lack of ego, at least when it came to executing and promoting (or failing to promote) his work. The problem is that authenticity is entirely inimical to the status quo we’ve already mentioned. This is why my father’s version of authenticity was refreshing – it projected an alternative way of being which some sought to emulate, others to exploit.

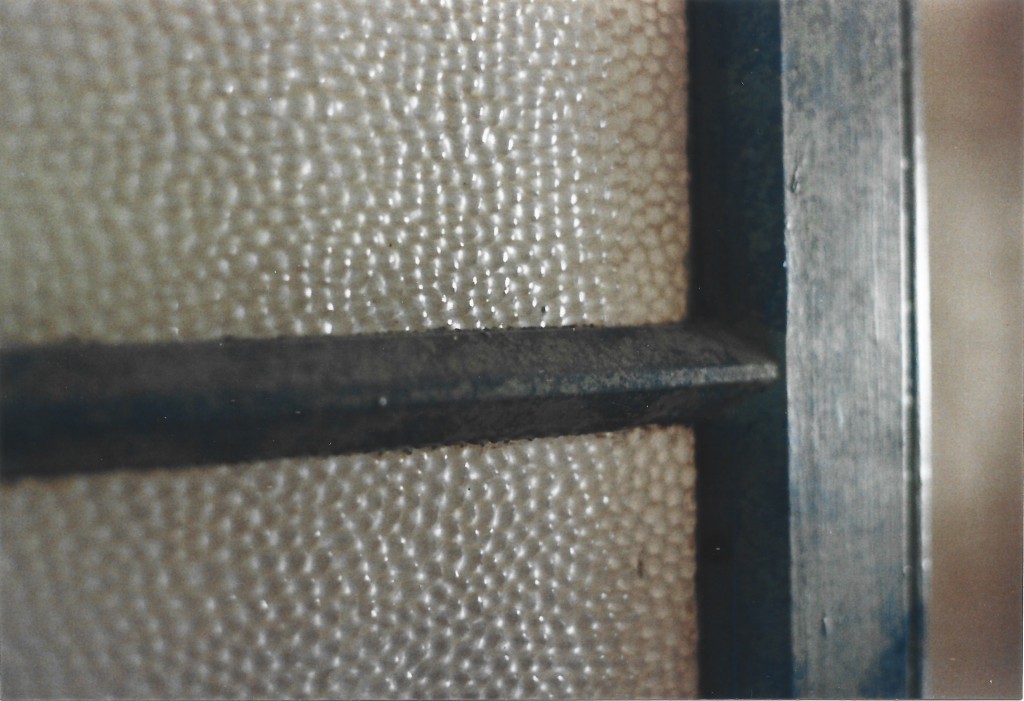

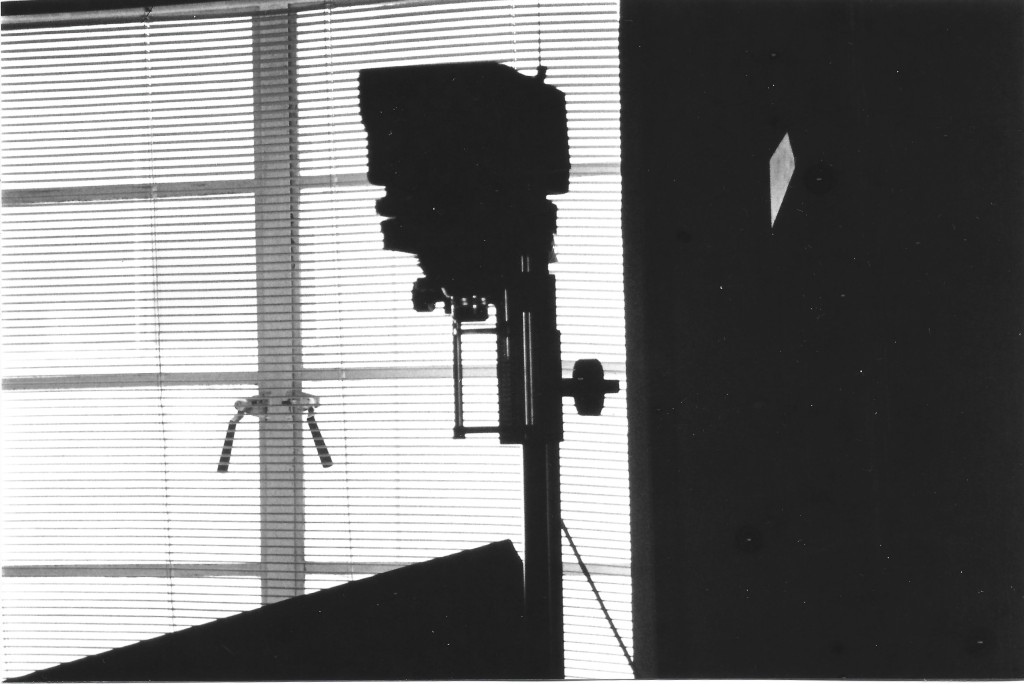

Never mind that all the features which people were quick to romanticise about my father, came to the fore only a decade or so before his passing. He dove back into photography in earnest after my mother’s stroke. Always in search of low-hanging-fruit solutions to make some money while still catering to his creative instincts, he started giving workshops to an eager gaggle of hipsters (yes, the term still had currency back then), and it was from there that the whole Zvez vibe became a thing; that darkroom and oak table occupying an iconic space in the memory for many, hipsters and not.

But, faced with the imminent need to vacate his apartment, I was also faced with old family photos. They command more attention from me than his subsequent, lauded works. They are the propulsive energy of the waters beating against the dam. They tell of a life lived – of a struggling immigrant family, and of a man still plugged into the churn of day-to-day life. Put-upon and frustrated, sure, but certainly not relegated to a cave of his own making, gawped at by those with a hole to fill, the crowd that real friends with real love have to machete through for a glimpse of my father’s attention.

They deserve space and time, and that’s why I’ll end it here from now because there are no neat endings in this process, only hard-won new beginnings.

***

Photography by Virginia Monteforte

Pingback: Tom Ripley Is An Author | Soft Disturbances