I.

Is there a standard expectation of when our earliest memory is expected to be? The image I have in mind feels a bit late in the day – I was six or seven years old – but I can’t grasp for anything earlier with any conviction and anyway, the further down you go the risk of low-key hallucination – our own personal storehouse of fiction – increases exponentially.

We left Serbia for Malta when I was seven years old, and we spent some days in Bulgaria en route to the island, because wartime sanctions meant we couldn’t fly out directly and had to make a pitstop to Sofia, taking a train ride from Belgrade and sleeping over at the home of acquaintances I hadn’t heard about before or since.

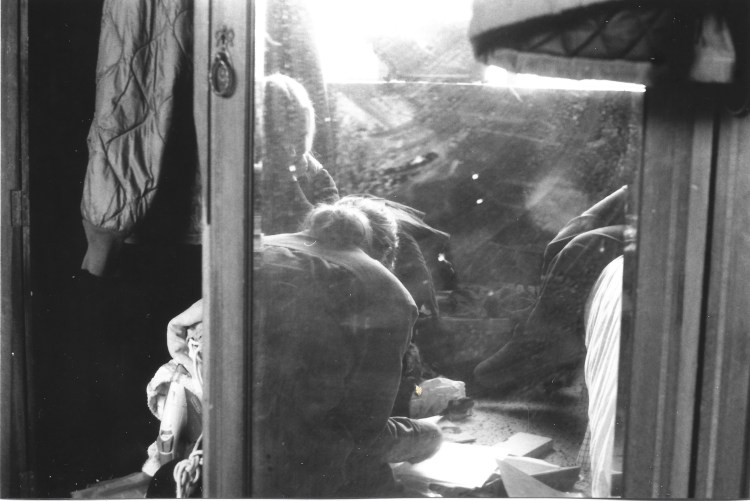

I do remember parts of Sofia – a large, Communist-style statue of a male figure seeping through the urban sprawl, a vegetable market, the brutalist buildings that weren’t all that different from Belgrade – and I remember the train ride too: though the sequence and the images aren’t that clear, my maternal grandmother’s sorrow and confusion still lands like a fresh arrow.

But these weren’t the very first memories – hazy and ancient though they feel too, like watching a grainy film of somebody else’s life, lost in archival wreckage and only just about salvagable, albeit in fragmented form.

The first memory was a foreshortened view of my mother – stylishly dressed as she always was, but definitely dressed to go out, with a coat and a hat and everything, and a wide, warm smile that was to become an aching pull of charm to whoever would meet her.

“We’re going to go find dad.”

She was foreshortened because I was sleeping on the top bunk of our bed in Zemun, with my four-year-old brother on the lower one. The mood of her smile suddenly matched my own – it spread out to me like an infectious carrier of pure joy.

Finding dad was the one thing I wanted. The one thing I felt was missing. The wistfulness for him that had become my norm by then was finally going to find its culmination, was finally going to be allowed to die a natural death.

So that I could become me, in whatever was left.

Dad wasn’t around for a bit because before the Malta plan, there was the Libya plan. The creep of the Yugoslav Wars – that one blip in the otherwise end-of-history-ish vibe that permeated the West during the ’90s – had nudged our parents into considering other options.

And the one that made itself readily available was this one: my father would go to work for his uncle at the drydocks of Benghazi, and the first stage of that was an exploratory trip away from us for some months.

The surge of instant gladness I still remember feeling the moment my mother smiled up at me to say we’re going to find dad means that I had felt his absence like the undeniable cavity of a freshly pulled out tooth.

There’s something that invokes self-pity in the idea that a lack was a main characteristic of my psychic development at that time, but there’s also a positive flip-side to this early memory being tinged with relief and expectation. It’s also a confirmation of the kind of bond you develop with a parent so early on – they really are at the center of your world, so their absence feels, at the very least, like a key comfort denied.

Now my parents are both dead. What to do when that absence becomes not just deferred, but extended indefinitely?

The more time passes, the more I realise just how much of that initial childish separation from my father conditioned my emotional space.

It made me all the more keenly susceptible to nostalgia, to the point where people would make fun of me for wallowing in it at such a young age. (“You’re seventeen, what could you possibly be nostalgic about?”).

Because my parents were either incapable, or unwilling, to internalise the value of sitting still. Displaced from Serbia, we moved within Malta too, just about enough to fully rattle my young psyche into believing that I’ll never find a true sense of home. It’ll surprise precisely no-one that the upshot of this was a dovetailing into fantasy by default.

During break-time at at school, I was magnetically drawn towards the areas of the playground market ‘out of bounds’ – signs virtually unenforced by whatever passed for gatekeeping authorities – lax at the best of times – and which were certainly not going to clamp down on the gawky, floppy-haired nerd who did little except munch of a soggy sandwich and stare into space.

Nostalgia and fantasy walk hand in hand. This is why nostalgia is more than just dry record or a verifiable memory. This is why it comes with a charge of desire and wistfulness, and consequently also why it tends to be viewed with suspicion. Unhealthy, neurotic, escapist and regressive. Putting people inside hamster-cage loops of the past that are both ghostly and undeniable.

This is all well and good. It is the rational position to take. It is the sober and constructive approach that discourages needless and ultimately damaging wallowing. Being lost in the past means being placed in a state of arrested development. Nostalgia means being plunged back into the past, but time as we live it moves forward, and a lot of our psychic success hinges

on at least meeting it halfway.

But that implies that a ground of some kind exists. A home base – indeed, a home, period.

But what if your home never quite materialised? And what if this tenuous home is a rock in the middle of the sea that is constantly made to evolve according to the whims of its colonising forces – both imperial and capitalist?

II.

Both my parents are now dead, and of course I have plenty of regrets and unasked questions which will forever remain pending in a rotting pigeon-box; snuck in but unopened, and I’ll soon forget the actual articulation of these questions and everything will join the same ghostly realm of the nostalgic miasma that I’m straining to pin down and describe here.

As we’ve said – time moves forward, and this forward motion also implies the scalding away of the bodies of those who gave you life and who – inadvertently or otherwise – shaped your social and emotional expectations. But these expectations are never perfect, and often in fact emerge from a build-up of keen and unique damage: unprocessed and even barely addressed.

You know all this. We know all this. But the forward churn of time often leaves these scars lodged into our bodies while we’re forced to tend to other, fresh ones. To put out new fires while older ones are still raging, though some may be reduced to a slow, keen sputter that has morphed into a fireplace of sorts.

I’m overreaching with these metaphors, maybe. I’m just sculpting verbal play from immediate impressions, in the hopes that it would yield something useful. But in the end, isn’t that what all writing is? Isn’t that what the essay form is in particular – to assay, to try, to learn as you go along.

Besides, I like the old-flames-as-new-fireplace metaphor. I think it speaks to the tendency of ‘legacy-trauma’ becoming a default state. Something to return to. A toxic form of comfort. Stories we tell to root ourselves into a sense of coherence, if nothing else.

One of these fireside conversations could concern the details of my father’s time in Libya. He was there around 1991 and 1992 – it had to be around the first half of that time period because by July of 1992 we had already ‘settled’ into Malta with the same provisional air that would inform pretty much everything else we would do as a family.

He was meant to work at the drydocks there, but that plan obviously did not work out because we ended up starting a new life in Malta instead. (There would’ve been something divinely ironic though, wouldn’t there, in going from one country with an authoritarian wartime crisis that devolved into civil war, only to find ourselves in another further down the line).

The fireside story is that he was given a reprieve from whatever hands-on work he was expected to do and he was sent to ‘deliver documents’ to people in Malta. He never got too specific about either. And I never really felt the need to ask, for some strange reason. It’s not so much that I feared the answer would yield something suspicious or unsavory. It’s just that at the time, I took his word for it. I guess we all did. It’s just the kind of thing you allow dads, I suppose, because you want to submit to that imperative – to believe they are the ones providing you with that stable bedrock from which all other meaning emerges and grows.

The fireside story isn’t so much about what he did and didn’t do there, exactly. For that, I suppose there’s both the prosaic and the spurious – if not romantic – interpretations available to us to bandy about.

He could’ve just decided it wasn’t for him – any by extension, per the aforementioned patriarchal imperative, not for us – and that he made a judgement call and opted for the post-colonially wrecked but pretty Mediterranean island instead. Then we could of course run riot with the poundshop espionage narratives, the lurid conspiracy theories: ‘delivering documents’ from Libya to Malta at the peak of the Gaddafi regime? Juicy. Le Carre worthy. Even ‘sus’.

(Later, much later, as my brother and I would bond over his many faults and wounds after his death, he’d offer a plausible stitch to the story: our artsy father was ‘useless at actual construction work’ and so his uncle found some use for him as an messenger boy).

But funnily enough, the fireside story doesn’t amount to a culmination of any of the above. It concerns an even more finely-tuned and concise piece of storytelling. One that frames our tale of settling into Malta as both sanguine and inevitable.

“My dad went to work in Libya, he didn’t really like it, so he took a Captain Morgan boat to Malta to scope out the island and once there he said, this is good – we’ll settle here.”

An elevator pitch. Free of needless detail and complication. Emboldened with pure immigrant pluck, and animated by hope.

Just like we never questioned the details of my father’s time in Libya, so my family never picked all that much at the thorny matter of the Yugoslav Wars, at least not in any incantatory way that would cohere a united front – those micro-political stances some families do take on major issues like these. It’s not that the subject was taboo – my parents spoke about it among themselves in our presence, openly discussing it with fellow Yugo-expats while trying to condense it into bite-sized chunks for Maltese acquaintances – but there was a sense in which talking about it at length with the kids meant infecting the family with its oozing ugliness.

There were some tableside scraps of the narrative which were easy to internalise, though: such as the prevailing thought that the very premise of the war was absurd, that the internecine divisions which characterise it were arbitrary and that nationalistic impulses in whichever direction were enabled by a lumpen mass of the uneducated.

But on a day-to-day level, the war only registered in the undeniable fact of our displacement, and our ongoing distance from the home country as it all raged at its worst and sanctions still barred us from traveling.

So that we lived in that absurdist limbo state where Bryan Adams’s ‘Everything I Do (I Do it for You)’ – ubiquitous as the equally incorrigible camp-fest that was Robin Hood: Price of Thieves to which it was wended as the banner theme song – edged itself into our lives in a more significant way than the contemporaneous Battle of Vukovar never could. Similarly, when we finally got to return to Serbia in 1996, the main emotional undercurrent was that we got to introduce my sister – born a year prior – to our grandparents… us kids were oblivious to the fact that the Dayton Agreement is really what made the trip possible.

‘The war’ was just a perpetual hum in the background of our lives: an undeniable state whose particulars, however, were always remote for us in the immediate sense.

I suppose this is the privilege of those like us who made their way out. (Not to mention the position of Serbia in particular, when it came to its role in the conflict itself).

But there are so many remainders and loose ends. No real narratives, only impressions. And I suppose that, when it comes to war, this is all for the better: we know that concrete narratives in these scenarios often breed monstrous things.

But for a child, the space of silence is rarely a cocoon for meditation. More often than not, it becomes an incubator for loneliness.

III.

The space of loneliness is of course different from that of solitude – with the latter assuming the mantle of the heightened position, the zen-like placid calm and an easy self-communion – but when you’re a kid and experimenting with the things that make you feel good and ease the pain you don’t yet have the layers of experience, of trial-and-error to really make the distinction.

I’ve spoken a lot about the in-the-moment dynamics of displacement and migration here, and loneliness – crucially, not solitude – was a big part of it for me from the beginning since there was very little to latch onto or even land on.

This is what I’ve always found funny about Malta. That the rock is totally a rock. Its undeniable state as an island predominantly defined by rock and STONE – largely the flaky-soft limestone, but still. Famous for it Neolithic temples and famous for all the subsequent temples that followed – one church for each day of the year, St John’s Co-Cathedral and Ta’ Pinu Basilica and all the rest of it. The winding country roads defined by handmade cobbled walls – precarious as they are ubiquitous, a trademark to be protected and which will determine the island’s definition for what feels like forever.

And even down underground, from the paleo-christian catacombs that snake their way across the north, the old water cisterns now fit for dark-tourism-lite tours and boutique concerts, and of course the Hypogeum: now barely reachable by the masses keen to visit all year round because the tickets prices have shot up just like everyone else…

So many perfect enclaves. So many stone spaces to snuggle up against. For shelter, for reflection… to count each crack and each pock-mark, if you like. To be guided by flaming torchlight down subterranean a subterranean passageway and then, reach a clearing and drop it down to the humid floor, and what follows will either be a period of meditation or its longest culmination – death.

But it doesn’t happen that way, does it? Instead of the earthy, enveloping powder of the pure stones by day and its chiaroscuro promises as the sun goes down, the island actually fights against itself and becomes louder and louder – taking the advice to rage against the dying light just that little bit too literally to tip it all over and ruin any remaining chance of peace.

The rocky enclosures are just the kind of spaces I would dream about when I’d head down to lunch break at Ħamrun Liceo; a place where I eventually did find friends but whose long stretches were defined with simply wanting to be elsewhere and assuming this was normal.

Shaping yourself into someone who tolerates life means negotiating the space between the physical and the non-physical, and when you’re raised by parents too scattered and frayed on their own end to offer a ballast or groundwork beyond the most rudimentary, your grasp of the non-physical is equally all over the place.

This is also the same absurd space where Bryan Adams hit anthems co-exist with the news of the Battle of Vukovar, that hum which cannot shape itself into anything coherent, let alone stone.

So, home. Malta became home. We were ‘third-country nationals’ for the longest time and then, one day in 2012, we weren’t any more. A couple of years after my mother had a stroke that would land her in a coma for a decade, we were finally mailed that much-desired olive branch: citizenship.

My father, brother and I went to the office and read out a declaration and signed a paper. The burly policewoman behind the heaving-with-documents desk pointed to another small but significant feature: a crucifix. “Catholic?” she asked us, and when we nodded no she made no fuss about it and just made us read the secular take on all this – said declaration that we would loyal to the Maltese state and respect its institutions and blablabla – and that was that.

We went back home after that, what for both my parents remained a forever home owing to their premature deaths, and what in any case for us was the longest-running home we’d known by then.

3A, Panorama Flats in Sliema. It was something of a purgatorial wreck by that point, owing my mum’s long sojourn in hospital, and then a care home from 2010 to 2020. As us kids trickled out bit by bit, my father would eventually rebrand it into a workshop space-cum-artist commune.

But in that crucial moment in 2012, it was still something of a gutted mess: we were living like roommates – as my father would take pride in saying, sloughing off any leftover parental responsibility he may have still felt beholden to – hypnotised by the puzzling absurdity of our present situation.

My mother was a beautiful, creative young woman who was holding a bunch of stuff together, and her presence in the home – this apartment, the likes of which they don’t make anymore – was a huge part of that: from its inspired decor, down to her expert hand at entertaining a varied panoply of guests, mostly culled from what would pass for something resembling a bohemian strain to Malta’s doggedly provincial social scene.

After she was gone, there was a period when the house simply took on a life of its own – where our respective rooms became cocoons and we would barely cross each other’s paths because making excuses to not confront the core realities of it all was what we’ve been taught. Our parents always gave us the impression that life was simply TOO MUCH – that there was always too much to do, that we were always too broke, that they were always too tired and too stressed for us to be adding to any of that with our own problems.

So I began to view the parties they would organise in the same way that they would – a reprieve from the inevitable, native stress that resided in all our hearts – and which subsequently exploded their own – and we could join in because, after all, we were all just roommates, right?

The permutation of Panorama into a new space for more roommates speaks to my father’s inability to move on from the ingrained idea that this apartment would be the only forever home he would allow himself, despite the residue of all the ghosts it still contained – the same ghosts he never had the gumption to confront with any real sense of finality and articulation. Speaking to one of the roommates who would subsequently populate the space – this one in particular residing for a while in what used to be my room – revealed the extent of this: “Cleaning that place to the end was impossible. There was always some rot, some mould that just wouldn’t go away.”

Apply all of the psychological cliches you can think of here: a man loses his wife and cannot muster the strength or courage to get up off his ass and leave the home they built together, and after his kids fly the coop he populates it with new kids so as to be able to exist in a version of the same patterns he was used to and thus, keep the inevitable at bay.

This is why I feel drawn to a darkened catacomb as a culmination of everything. This is the emotional legacy I’m labouring under, if we are to passively accept that we all become our parents and simply follow in their footsteps.

The fact is, however, that home is not a static object. My mother reaching out to me in the bunk bed and telling me “we’re gonna go find dad” meant that we were leaving a home to find a more permanent one – one in which the cavity of my father’s absence was no longer felt.

This emotional space is slippery and prone to unfortunate dependencies. You rely on your parents, for example, to continue carving out that space of security for you, but my own were never really able to do that, so what was left for me was my own headspace – the generous reading: ‘Mind Palace’ – where I had a degree of control and I could craft things my way, but whose particulars also inevitably pulled from existing surroundings.

The danger lies in getting tired. If you’re tired you’re more prone to lie down, and to lie down you need a solid surface that will accommodate you. So this is why you craft the idea of home as a solid space to return to and just lie down in. But without a sense of cultivation, when all that’s left is rot, home becomes a prison.

Working through this, I suppose the grandiose take is that it’s all about forward motion and sudden death. Moving from one place to a better one and then being drained my life so that you’re felled in the same spot in which you’ve tried to make a home.

When you’re felled, you’re alone. And you either die there or you achieve genuine rest.

Soon after we got our citizenship, I took advantage of my newfound privilege as a European citizen to cross a fraction of the continent on my own steam – taking a three-week trip across London, Edinburgh, Prague and Berlin.

When I came back to Malta, it was September and despite the heat, I decided to go on a solo hike up north. I failed to adequately follow a walking tour guide offered by the Malta Tourism Authority – my map-dyslexia is maddeningly legendary – and ended up prolonging my journey to a ridiculous degree.

But trekking along Dingli Cliffs while listening to Popol Vuh’s soundtrack to Werner Herzog’s ‘Nosferatu’ was transformative. The heat was of course doing my head in, quite literally in many ways, but I didn’t care.

The strumming sitar sound, the yellow stones and the occasional abandoned shrine to the Madonna. Increasingly irrational, but it was a communion with the space that I hadn’t really felt before or since.