As I’ve mentioned in my last post, December took it upon itself to welcome me with a nasty sucker-punch of the flu: a freelancer’s nightmare in a season when all the clients want things done in bulk so that everyone can rest up during the holidays.

But one upside of it all is being able to soak in all the stuff I would have soaked in otherwise, but with an added single-mindedness… partly owing to the fact that I could do little else and so was justified in spending days on end just reading and watching things.

So here are some recent things I’ve consumed and enjoyed during that period… though some of them were either consumed or begun before the illness hit. Either way, feel free to allow them to double-up as gift ideas. Am sure the indie creators on the list would appreciate that especially.

Creatures of Will and Temper by Molly Tanzer (novel)

Creatures of Will and Temper by Molly Tanzer (novel)

I was never too keen on the ‘& Zombies’ sub-genre of literature, if we can call it that. It just seems like such a one-trick-pony gimmick that to spread it out over an entire book — much less an entire unofficial series of them — just struck me as a bit redundant and silly.

Having said that, I did enjoy the Pride and Prejudice and Zombies film, in large part because director Burr Steers deftly shot all of it as a Jane Austen pastiche first and foremost, with the zombies having to blend in with the established ‘heritage film’ mise-en-scene, rather than overpowering everything into pulp madness once they do show up.

Rest assured that Tanzer’s novel — a meticulously put together gender-swapped take on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray — owes very little to the ‘& Zombies’ trend, save for perhaps this last element. When the supernatural element does rear its ugly head, it does so in world with firm period rules already established, and in a story about sibling angst that stands front-and-centre for the bulk of the running time.

The result is an experience that is both immersive and captivating; a Victorian pastiche and tribute to the legacy of Wilde that very much scratches those familiar itches, while also offering a fun, pulpy comeuppance in the end.

***

The Man Who Laughs by David Hine & Mark Stafford (graphic novel)

The Man Who Laughs by David Hine & Mark Stafford (graphic novel)

The last thing I did before getting sick was attend Malta Comic Con 2017, and a fun time that was indeed. Meeting old friends and new under the spell of our geeky obsessions is an experience that’s tough to beat. I also spent an inordinate amount of money on comics and artwork and no, I regret nothing.

Particularly when it concerns undeniable gems such as these — a work that once again draws on a literary classic, though one certainly not as universally lauded as The Picture of Dorian Gray.

As writer David Hine writes in an afterword to this adaptation of Victor Hugo’s L’ Homme qui rit — perhaps more famous for a silent film adaptation starring Conrad Veidt which in turn inspired look of Batman’s arch-nemesis The Joker — the original novel, a late-period Hugo miles away from the populist charm of a Les Miserables, is something of a convoluted, knotted beast whose socio-political digressions he’s had to cut down to ensure the story flows as well as it can.

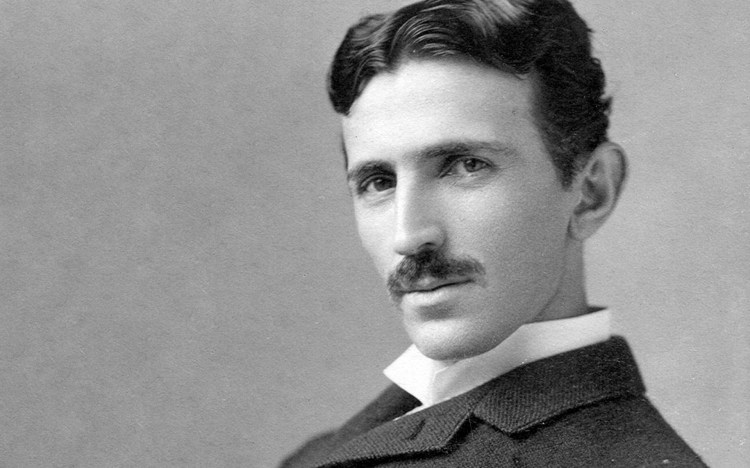

Mark Stafford, ladies and gentlemen

Stripped down as such, and aided by tremendous illustration work from artist Mark Stafford, the volcanic melodrama at the centre of the story — and it is a melodrama, though perhaps in the best possible sense of the word — is allowed to come to the fore, and I practically tore through the pages as my heart raced, yearning to discover the fate of poor perma-rictus-infested Gwynplaine and his fragile adoptive family.

Stafford’s work really is tremendous, though. His grasp of the grotesque idiom works to highlight both the social horror and sublime tragedy that frames the whole story, and the chalk-like colouring technique adds that something special to the feel of each page.

The assured lines and deliberate exaggerations brought to mind the work of Lynd Ward, and in any case — here’s a story that definitely shares some genetic make-up with God’s Man, dealing as it does with the venal, compromising nature of the world.

***

Winnebago Graveyard by Steve Niles and Alison Sampson (comics)

Winnebago Graveyard by Steve Niles and Alison Sampson (comics)

Collecting all the single issues of the titular series, this is another gorgeous artefact I managed to pick up at Malta Comic Con, this time from its affable and keenly intelligent artist, Alison Sampson, who was kind enough to sign my copy over a chat about the comic’s intertextual DNA of ‘Satanic panic’ and folk horror.

It’s a lovely-to-the-touch, velvety volume that comes with generous backmatter expounding on the same DNA, but what’s in between isn’t half bad either.

A simple story about a family being shoved into a deeply unpleasant situation — i.e., an amusement park that dovetails into a Satanic human-sacrifice ritual — is elevated away from cliche by Sampson’s art, which flows from one panel to another — often letting rigid panel divisions hang in the process, actually — in a grimy-and-gooey symphony.

***

Thor: The God Of Thunder (Vols. 1 & 2) by Jason Aaron & Esad Ribic (comics)

Thor: The God Of Thunder (Vols. 1 & 2) by Jason Aaron & Esad Ribic (comics)

More comics now, though this one only confirms that I’m as much of a lemming to the machinations of popular culture as anyone else. To wit: when Comixology announced a discount-deal on a bunch of Thor comics in the wake of the brilliant and hilarious Thor: Ragnarok, I bit like the hungriest fish of the Asgardian oceans.

I’m glad I succumbed to this obvious gimmick, though, because it gave me the chance to catch up with this gem of a story arc, which gives us three Thors for the price of one, all of them trying to stop not just their own Ragnarok but the ‘Ragnarok’ of all the gods of the known universe, as the vengeful Gorr vows to unleash genocide on every single divine creature out there.

The two storylines out of the run that I’ve read so far — ‘The God Butcher’ and ‘Godbomb’ — felt like such a perfect distillation of everything that makes superhero comics work. A grandiose, epic story of ludicrously huge stakes, sprinkled with a necessary indulgence in pulp craziness (Thor on a space-shark, anyone?) which is in turn deflated by the strategic deployment of self-deprecating humour (the sarcastic back-and-forth between the Thors is a pure delight).

Ribic’s art seals the deal though. His gods certainly look the part — they may as well have been carved out of marble — helped along by the clean, gleaming shimmer that is Dean White’s colouring work.

While I eagerly look forward to devouring the latter half of the series, this rounds off a great year in Norse-related literature for me, during which I’ve enjoyed Christine Morgan’s across-the-board excellent The Raven’s Table from Word Horde, while I’m currently devouring Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology — a book that so far displays the popular myth-maker’s slinky and pleasant way with words, if nothing else.

***

The Punisher (TV)

Another Marvel product that needs no signal-boosting for me, but which I found gripping enough through its 13-episode run, for some obvious and less-obvious reasons. Yes, updated as it is to insert a too-easy critique of the American military-industrial complex (though really, only of its “bad apples”), Frank Castle’s adventures offer an easy cathartic kick.

As the title character of another show I love dearly — far, far more dearly than The Punisher or anything else for that matter — would have it, “Doing bad things to bad people makes us feel good“.

But that wasn’t what stayed with me. What stayed with me was Frank’s very nature as a “revenant” — he’s even referred to as such by another character at one point — and how that’s hammered home by the fact that he’s made to operate from an underground lair as his true self, but that when he returns temporarily to the surface, it is as if he were alive again, but only when he wears his new disguise.

A mythic touch in a story that revels in its supposed grittiness, and a welcome one too.